|

| My Grandfather, on guard duty at his Kibbutz, 1939. |

WARNING! Researching dead relatives can be a lonely endeavor. If you are thinking of researching your family history, consider yourselves duly warned. The genealogist amongst you, surly know what I'm referring to. For the record, please note: as difficult, frustrating and lonely as this pursuit may be, I HIGHLY RECOMMEND GENEALOGY!

Personally, I am far from sharing Tim Tebow's religious beliefs—and as a Bostonian, I could not be happier that the Patriots just ended his amazing run—but I share in his message: Never Give Up and Good Things Will Come. Genealogy is a form of detective work requiring spending long hours alone, perseverance, attention to details and exceptional deciphering skills. Those around you, will rarely understand this crazy obsession with the past. Luckily, for you and for me, the internet is full of other's like us. The good news is, there are millions of Americans—and many more millions around the globe—researching their family history. In my immediate family, everyone is far to busy living their lives. Justifiably, they have little interest or time to study the lives of those who came before them. Yet there is a whole community of professional genealogist or self declared genealogy addicts who are out there sharing their work, offering advice, posting blogs and supporting this amazing and important process. While the process can be frustrating and guaranteed to lead you into many dead ends, I promise it's a journey worth taking. To illustrate how perseverance will result in great discoveries, I want to share with you one of my most remarkable discoveries: records in the Yad Vashem (Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority museum in Israel) database exposing information I feared lost forever. Read on, and remember DON'T GIVE UP!

It was two o'clock in the morning, and once again, I was staring at my computer screen, looking for clues about my great-grandparents who died in the holocaust. Four of my eight great-grandparents, lost their lives prematurely in the holocaust. My father, lost all his grandparents before he was born. So little did my grandparents talk about their lost family, that my father—now in his sixties—just did not remember the first names of his long deceased grandparents. "How can you not remember your own grandparents names?" I kept asking. They were people, full of life! They were trapped by history. Living in the wrong place, at the wrong time. Someone needs to remember them. These missing ancestors were a huge hole in my family tree and my heart. All I had to go by, was their last names. Yampel and Celnik.

|

| My Great Uncle William Celnik who Survived Auschwitz and his wife Edith Rose. . |

I must have searched the Yad Vashem site hundreds of times prior to that night. I searched there and on many other sites, ancestry.com and JewishGen to name a few. Without a first name, or any other identifying clue, it is almost impossible to identify a lost one. I kept probing my father for information and insisting that there must be somewhere we can bring to light the names of his grandparents. After all, they were his grandparents, not some distant relative. Earlier that day, my dad walked in triumphantly and said:" I found some documents. I hope they help." In his hand he held two death certificates belonging to his parents. My expert eyes scanned these documents in amazement, and immediately picked up a very important fact he had completely over looked. Both death certificate, written in Hebrew, listed the name of the deceased's fathers: Leon Yampel and Matias Tzelnik. Finally, I had names. This was a huge breakthrough! Armed with this new information, again I entered YadVashem.org, hoping to discover something about the two men who gave me life, and whom I knew nothing about. I looked and I looked. Nothing. I tried different spellings. Nada. And then, as I was about to call it a night, I noticed an option on the search engine which said witness.

It took a little more exploring to understand what this witness option was all about. Yad Vashem, collects testimonies of holocaust victims. These documents are called Witness Pages and are a kind of combination of a birth and death certificate. Despite the German's compulsive record taking practices, millions died during the war without a trace. The Witness Page is a testament to these victims lives and the fact that they existed. Normally these forms are completed by a relative or person who knew the victim and therefore witnessed their life. I had an epiphany. My grandfather, must have documented losing his parents, brother and in-laws.

When I saw the witness option, on the Yad Vashem search engine, I knew that my grandfather, with his dedication to documenting the holocaust, must have filed a testimony page in Yad Vashem. Instead of looking for Yampel or Tzelnik, I tried a new approached and searched for Baruch Lavi, the witness. (My grandfather, Born Zigmond Yampel, Hebrewtized his name, around the foundation of the state of Israel. This was another attempt to leave Europe behind). To my amazement, instantly, sixteen records appeared. I looked at the list of names, and there they were. My four great-grandparents, and four great-aunts and uncles, each of their name appearing twice. I clicked on the first one, and read the summary. Then I clicked to see the original document. What I unearthed, was a Witness Page filled out by my grandfather in 1955. By then, after years of searching, he must have given up hope of finding survivors. This document may have been the only piece of closure he had. His familiar hand writing, recorded his fathers name, Leon Yampel—transcribed Jampel (J is pronounced as Y in Polish, a fact I did not know at the time), no wonder I could not find it—date of birth, names of Leon's parents, occupation, last known address, and where Leon may have perished.

|

| Yad Vashem Witness Page for Leon Jampel my great-grandfather |

|

| My grandfather's brother Michael Jampel Who perished in the holocaust. He was about 12 years old when he perished. |

|

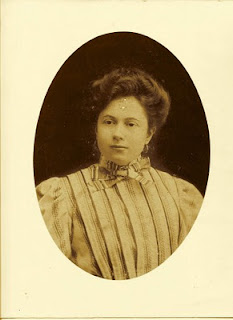

| My great-grandmother Anna Celnik (Rosenbloom) Holocaust Victim |

|

| William Celnik's Auschwitz uniform (photo curtsey of Massuah) Note the red triangle overlaying the yellow triangle designated him as a political Jewish prisoner. |

What has been your most amazing genealogical discovery? Please share with us in the comment section. Have you reached a dead-end? Do you need help? Write me a comment!

Wonderful post. It will help others keep searching even when they seem to hit a dead end.

ReplyDeleteGenealogical work advances in spurts. Then you hit a plateau and you feel it's never going to end. One thing I suggest moving to a different branch for a while. Then at least when you come back, you feel less frustrated and often find a new angel or a new database.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis story brought tears to my eyes. I completely understand what you mean when you say it feels like your grandfather left those witness forms just for you to find. What a wonderful gift.

ReplyDeleteMy great-grandparents emigrated to America before WWII. They had no idea they would lose every friend and relative they left behind. So much loss...

Thanks for the beautiful comment Barb. I think understanding the guilt and the burden they carried is very important. Their pain and silence affected so many of us in so many ways.

ReplyDelete